Africa in a post-aid world

The world, particularly the African continent, is still trying to understand the consequences of the freeze on foreign aid imposed by the United States. Donald Trump made this decision on January 24th, just days after his inauguration as President of the United States for the second time.

The ‘stop-work’ action imposed a 90-day freeze on foreign aid, except military aid. Even though some clarifications and exceptions have been made around that freeze, the reality is that adjustments have to be made around how to plug the gaps left by the end of USAID in terms of both money and expertise.

This data dive focuses on a few things: the givers of aid, the receivers of that aid, where that money goes, and to what extent African countries are dependent on aid in comparison with their budgets. It also dwells briefly on what comes next. Let us begin with the givers.

Givers and receivers

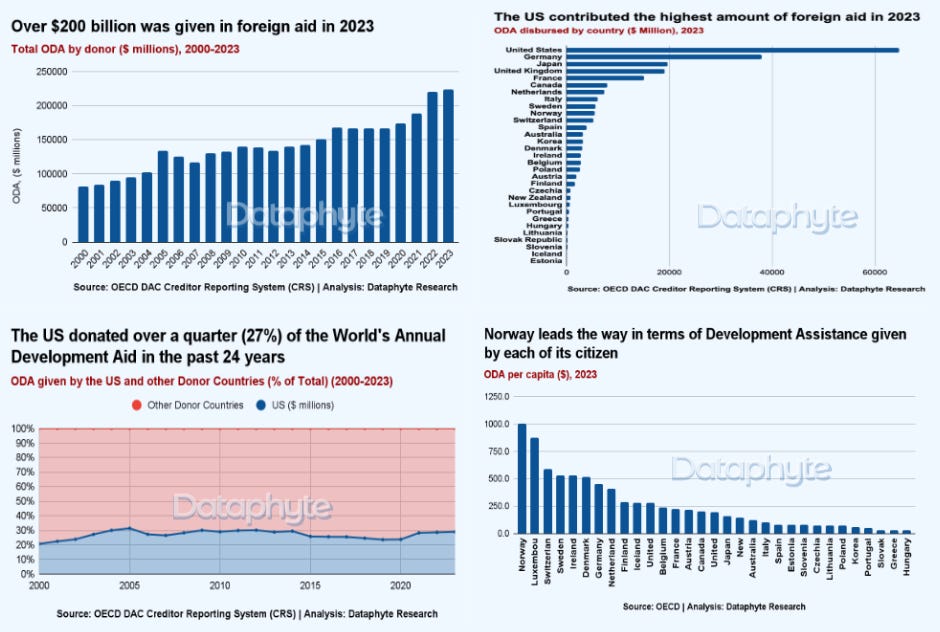

Total foreign aid or Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) totalled $223.3 billion, in 2023 according to ONE. The United States contributed 29% of that sum in 203, a proportion that remained largely unchanged over the last 15 years.

On a per capita basis, the Norwegians are by far the most generous givers of foreign aid, at over $1,000 per person. The US gives less than $200 per person and is ranked 17th.

Now to the receivers of foreign aid. On a per capita basis, the reception of foreign aid is dominated by small island states like Tuvalu and Tonga, while Ukraine ranks 9th.

If we focus on African countries, the island nation of Sao Tome and Principe ranks 1st in aid received per capita on the continent, followed by South Sudan. Algeria, Angola and Equatorial Guinea bring up the rear.

Let us now zero in on the USAID and how far its tentacles reached.

The USAID behemoth

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) is the primary vehicle for US foreign aid in the world and is considered by many to be a key part of projecting US influence abroad. It was created in 1983 by the Reagan administration and it funds multiple interventions across healthcare, humanitarian response, democracy and civil society and so on.

Between 2022 and 2024, Ukraine got by far the highest disbursement from the USAID, while Nigeria ranked 8th. In 2023, USAID disbursed $44 billion, about 1% of America’s federal budget. On its own, it would be the largest aid donor in the world. Ukraine received 36% of that. The top 10 had the usual suspects like Ethiopia, Somalia and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Nigeria ranked 8th.

Where does this aid typically go? The current largest category is Government and Civil Society ($17 billion), which is largely a shorthand for economic support for Ukraine. Humanitarian aid ($9 billion) and Health and Population ($7.4 billion) place second and third respectively. Prior to the Ukraine war in 2021, Health and Population ($13 billion) and Humanitarian aid ($6.7 billion) took up the bulk of the USAID’s $28.3 billion in disbursements for that year. The administration costs of the USAID are huge: $3 billion a year. The USAID is involved in activities in over 200 countries and territories worldwide.

Plugging the gaps

Nigeria has been fairly swift to plug the gaps that will be left by the end of USAID funding. Two concessional loans of $500 million have been secured from the World Bank’s International Development Association, as well as an additional $70 million from other international bodies. ₦4.8 billion was also approved by the Federal Executive Council for the procurement of 150,000 HIV treatment packs. In a recently released statement from the Ministry of Health spokesman,it was revealed that the shift in US priorities has been anticipated. This would explain the quick response to events.

Healthcare interventions have been the most effective example of western involvement on the African continent. From HIV to malaria and tuberculosis, these various interventions have saved countless lives. PEPFAR in particular has been estimated to have saved 25 million lives since its inception by George W. Bush’s administration in 2005.

Other African countries may find it difficult to replicate Nigeria’s swift response to policy changes in Washington DC, due to much smaller resources. Countries like South Sudan, Somalia, Eswatini, Djibouti and Liberia would find themselves under real pressure without US foreign aid.

However, the issues go beyond mere funding to the very real issues of logistics, planning and implementation that have underpinned healthcare service delivery in many of these countries while they have been run by foreigners. If this expertise has to leave, there is a question of if the local knowledge is there to replace it, and if local authorities have the wellbeing of their citizens at heart in order to deliver the same or similar quality of services. You do not need to look far to find evidence that this will be a problem: the scandal around electricity provision to University College Hospital in Ibadan is enough of a pointer.

In theory, you can drop a sack of money to replace US foreign aid, but that money still has to be translated into life saving interventions. To paraphrase one former football legend, I have never seen a bag of money deliver a vaccine, mosquito net or HIV treatment kit.

Africa’s place in a post-aid world

The actions by the Trump administration are likely to accelerate a move towards a post-aid world. The shuttering of USAID and laying off of its staff is merely the most dramatic occurrence, but the cut in US foreign aid is not an isolated event. In fact, there is evidence that shows we are entering a post-aid world. The tide is going out and it will soon be obvious who is swimming naked.

The biggest example of this is the Netherlands. Last year, its new government announced that its foreign aid budget will be cut by two-thirds, totalling €2.4 billion by 2027. With growing nativist sentiments leading to the rise of far-right, anti-immigration political parties and Europe’s need to increase its military spending to make up for America’s reduced commitment, we should expect more aid budgets to come under pressure. Cumulatively, European nations contribute $26 billion to foreign aid, according to the OECD Creditor Reporting System. It is not an insignificant amount of money.

In high-income countries, more and more people are questioning why resources are spent on people in far-away countries when those resources could be used better at home. The phrase ‘donor fatigue’ has been around for some time. Sensing this, some African leaders are beginning to talk about moving from aid to investment. At the World Economic Forum in Davos in January, Nigeria’s Vice President Kashim Shettima said that he believes in partnership, dignity and investment with developed countries, as opposed to the current dynamic of foreign aid. Those statements are in line with the Tinubu administration’s push to attract more foreign investment into the country.

However, Africa’s current standing on FDI does not make for pretty reading. In 2023, the entire continent attracted as much FDI as Indonesia. When a lack of state capacity is combined with corruption and overall complacency from African elites, the conclusion is reached that Africa is ill-prepared for a post-aid world.

That does not have to be the case. This change can serve as an impetus for the individual governments, political elites, and regional and continental bodies by extension, to have clarity on what they want for their societies, regions and the continent.

It is past time for various African states to increase their capacity to deliver basic services in healthcare, education and disaster response. These are areas where foreign donors have achieved dominance, often holding up entire systems.

The free lunch is coming to an end.

If you've read this far, now take 2 seconds to share: