About 2 million children suffering from severe wasting are facing life-threatening risks due to a shortage of funds for Ready-to-use Therapeutic Food (RUTF), which is critical for treating this most severe form of malnutrition, a report by the United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF) shows.

If these children are lucky, they may be salvaged. If not, the world might once again witness the loss of a generation brimming with untapped potential.

Child wasting and other forms of acute malnutrition are the result of maternal malnutrition, high cost of food, poor feeding and care practices, exacerbated by food insecurity, climate crises, limited access to safe drinking water, and poverty.

For a child suffering from severe wasting, the risk of death multiplies.

Childhood Crises

About 45 million children under five are experiencing wasting globally, a form of malnutrition, identified as the direct or underlying cause of 45% of all deaths of under-five children.

In Nigeria, under-5 children are wasting away at a rate of 6.5%, while 31.5% are stunted and 1.6% are overweight.

While the prevalence of these three forms of malnutrition has declined over the years, the warm and calm blood of innocent kids still silently fades.

As their bodies weaken under the quiet grip of hunger, it reminds us that steady progress has yet to reach the most fragile among us.

This is the harsh reality for children across Africa, yet the youngest in Nigeria suffer even more, with under-fives wasting away faster than the average child in Africa.

Mauritania has the highest percentage of under-5 children who are affected by wasting with Nigeria ranking 12th among the top African countries with the highest prevalence of child wasting.

About 34.2% of children under the age of five in Nigeria suffer from stunting, having a low height for their age, a rate that exceeds the African average of 25.5%.

UNICEF identified that wasting, stunting, and being underweight in under-five children are forms of acute malnutrition and are influenced by various factors. Rising inflation and food prices are jeopardising healthy diets, making it increasingly difficult for people in many countries to get food that meets their daily nutritional requirements.

Cost of Hunger

The fragile bodies of Nigeria’s under-five children tell a story of a deeper crisis.

A crisis that starts at the heart of the home—with mothers and fathers struggling to access food or afford the simplest nutritious meal to hold their bodies together.

When a mother’s plate is empty or her diet imbalanced, the effect flows directly to her child.

The nourishment she lacks becomes the child’s struggle—manifesting in stunted growth, weakened immunity, and a life shaped by the consequences of hunger before they even take their first steps.

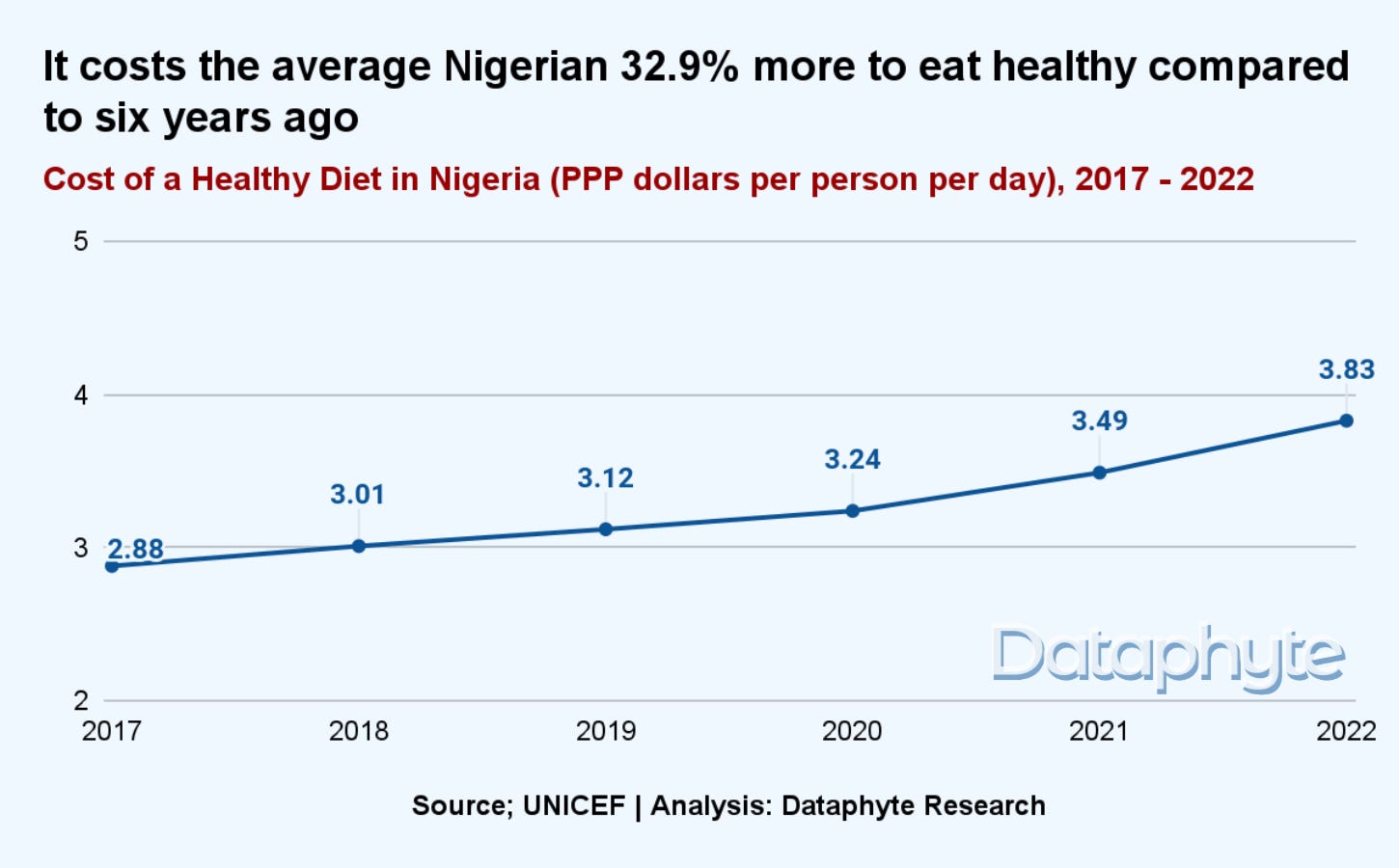

This is the reality of an average Nigerian who now pays 32.9% more each day to afford the cheapest healthy diet compared to 2017.

The cost of a healthy diet (CoHD) is the national-level estimate of the cost of acquiring the cheapest possible healthy diet in a country, defined as a diet comprising a variety of locally available foods that meet energy and nutritional requirements. The CoHD is then compared with national income distributions to estimate the prevalence of unaffordability and the number of people unable to afford a healthy diet.

As the price of a healthy diet increases, the proportion of people who cannot afford it also increased by 19% in the last 6 years, from 143.8 million in 2017 to 172 million in 2022.

When compared with its African peers, Nigeria ranks 16th in the cost of a healthy diet per person, which exceeds the continental average. This indicates that, on average, it is easier to afford a daily healthy diet in other African countries than in Nigeria.

The rising inflationary pressures on food and other items are also making nutritious meals increasingly inaccessible for households in Nigeria. A Dataphyte report noted that timely access to food is essential for children to reach their full potential, with the most critical period for good nutrition occurring during the 1,000 days from pregnancy.

As inflation drives food insecurity, the inability to access adequate nutrients poses a serious threat to many children's lives.

The inflation rate in Nigeria has experienced a steady increase over the last 16 years, reaching 31.7% 12-month average change in September 2024.

By the end of 2023, Nigeria ranks 9th with the highest inflation rate in Africa, surpassing the average for the continent.

Another factor contributing to malnutrition is poverty. The burden of maintaining a healthy diet frequently rests on the shoulders of the most vulnerable households. In Nigeria, 30.9% of the population continues to live on less than $2.15 per day, which is below the $3.83 required to afford a healthy diet.

This economic struggle leaves families with limited options, forcing them to prioritise quantity over quality when it comes to food. As a result, many children are deprived of essential nutrients needed for their growth and development, putting them at an increased risk of malnutrition-related health issues.

Wasting is the most urgent, visible, and life-threatening form of malnutrition, stemming from the inability to prevent malnutrition in the most vulnerable children.

Children experiencing wasting are excessively thin and have weakened immune systems, making them susceptible to developmental delays, illness, and even death.

According to a report by UNICEF, the incidence of wasting can surge dramatically due to conflicts, epidemics, and food insecurity, including challenges posed by climate change-related droughts and flooding. However, wasting is not confined to crisis situations; in fact, two-thirds of all children with wasting live in regions that are not currently experiencing emergencies.

“Although the number of children receiving treatment for wasting and other life-threatening forms of malnutrition has increased in recent years, only one in three children with severe wasting receives the timely treatment and care necessary for survival and recovery,” the report added.

The efforts to prevent and treat child wasting in most countries are often undervalued, underfunded and inaccessible, particularly for the most marginalised families and communities. In most cases, day by day, the frail bodies of these children fade silently, drifting further from the chance to thrive.