ICYMI: Borno, Flood and Blood

Borno State, the once peaceful state on Nigeria’s northern border with Chad Republic, Niger Republic and Cameroon is the epicentre of Boko Haram’s book-ban battles and decades-long bloodshed.

By 1:00 am on Tuesday, September 10, 2024, Borno’s twenty-two-year trademark of “Sorrow, Tears, and Blood” was updated to “Borno, Flood, and Blood.”

The spillway of Alau Dam in Maiduguri, the Borno State capital, collapsed after heavy rainfall, flooding the entire city and leaving half of it under water, displacing over one million people and submerging thousands of houses.

Unlike the lament in Fela Anikulapo’s song, on how “police and army” operations always leave a trail of sorrow, tears, and blood in communities, the lament in Borno now has a different cause.

The “home of peace” is caught in a crossfire of bullets and bombs on the one side, and renegade snakes and escapist crocodiles on the other - drowning livestock floating along and deadly beasts lurking in the murky waters of flooded roads, streets, and compounds.

Regardless of the cause, the police or the army, Boko Haram or Islamic State of West Africa Province (ISWAP), a broken Alau Dam or a broken accountability system, the familiar sword or a flash flood, the people’s lot is the same sorrow, tears, and blood.

The people of Borno grapple with economic losses, health hazards, and food insecurity in a long-drawn humanitarian crisis that has left its people displaced, destitute, or dead.

Borno

Borno, with the monicker, “Home of Peace,” was once just another state in Nigeria’s northern region, before its embers of forced ignorance, fanned into contempt for the liberties of education, sparked a bloody trail of violence that is yet to end. The state was the birthplace of the terror group, Boko Haram, in 2002 and has since become Nigeria’s headquarters of sorrow.

In 2015, at the peak of its power and territorial control, Boko Haram — which means "Western education is forbidden" — surpassed the Islamic State group (ISIS) in its terror and ranked as the world's deadliest terrorist group on the Global Terrorism Index. Since 2009, Boko Haram has killed tens of thousands of people in Nigeria and displaced more than two million others.

According to Human Rights Watch, 2023, “Boko Haram and its splinter factions, including the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP), continued to carry out attacks in the northeast and expanded their activities beyond the region.”

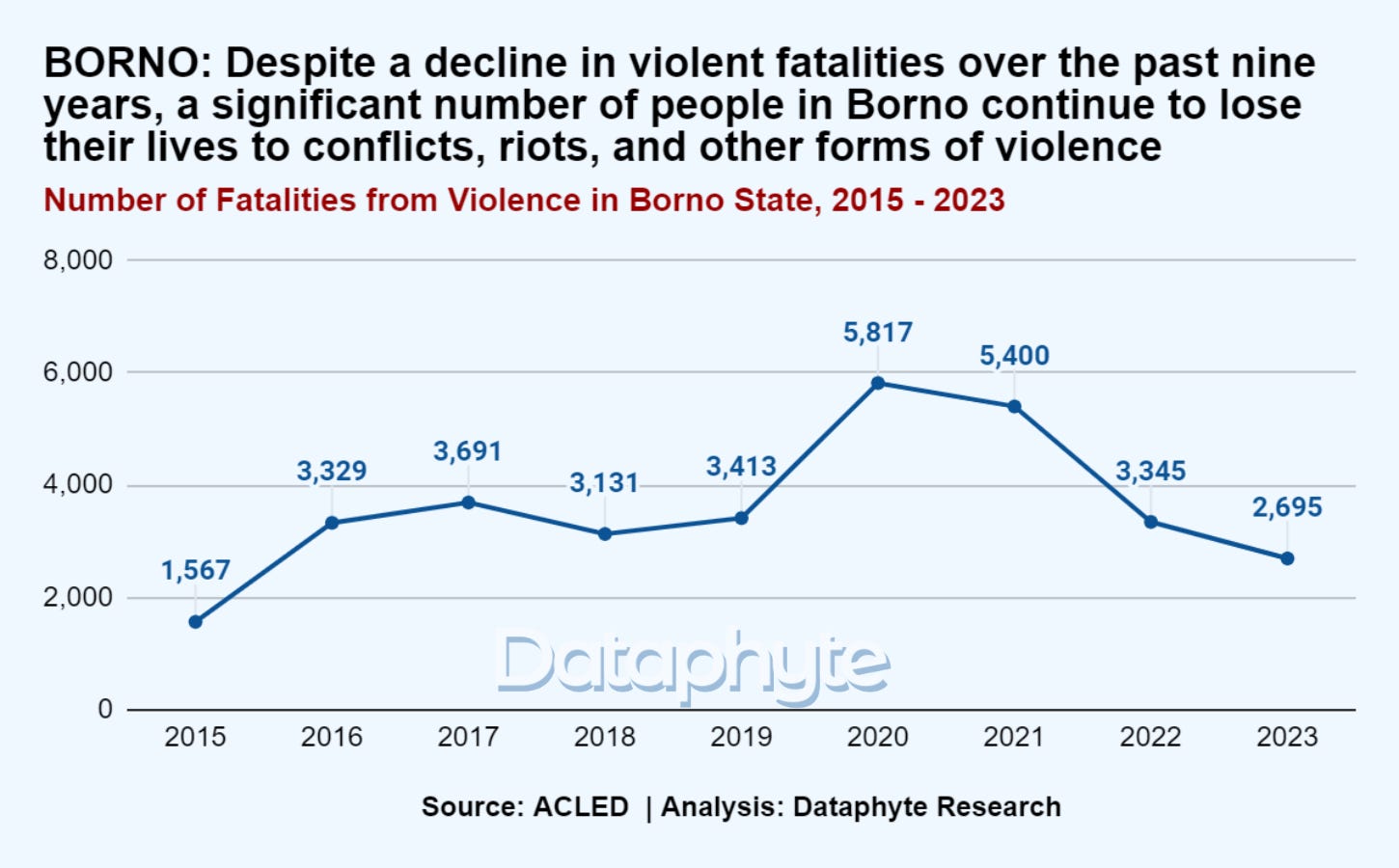

Besides attacks by Boko Haram in Borno State, other forms of violence—including riots and assaults on civilians by groups such as the Fulani Ethnic Militia, military forces, and communal militias—have claimed over 32,388 lives in Borno between 2015 and 2023.

When these forces of nature strike (material forces of nature such as a flood or material and mental force of nature such as a human), they leave behind "sorrow, tears, and blood - them regular trademark," as Fela Anikulapo Kuti aptly put it, resolving the mood in Borno in despair.

Flood

This time, the anguish in Borno had an unfamiliar face — a destructive force, unlike the familiar horrors the state had endured before - Flood!

The Alau Dam collapsed, and reports indicate that nearly half of the city is now submerged. Before 2024, the dam had broken thrice: thirty years ago, in 1994, in 2012 and 2022.

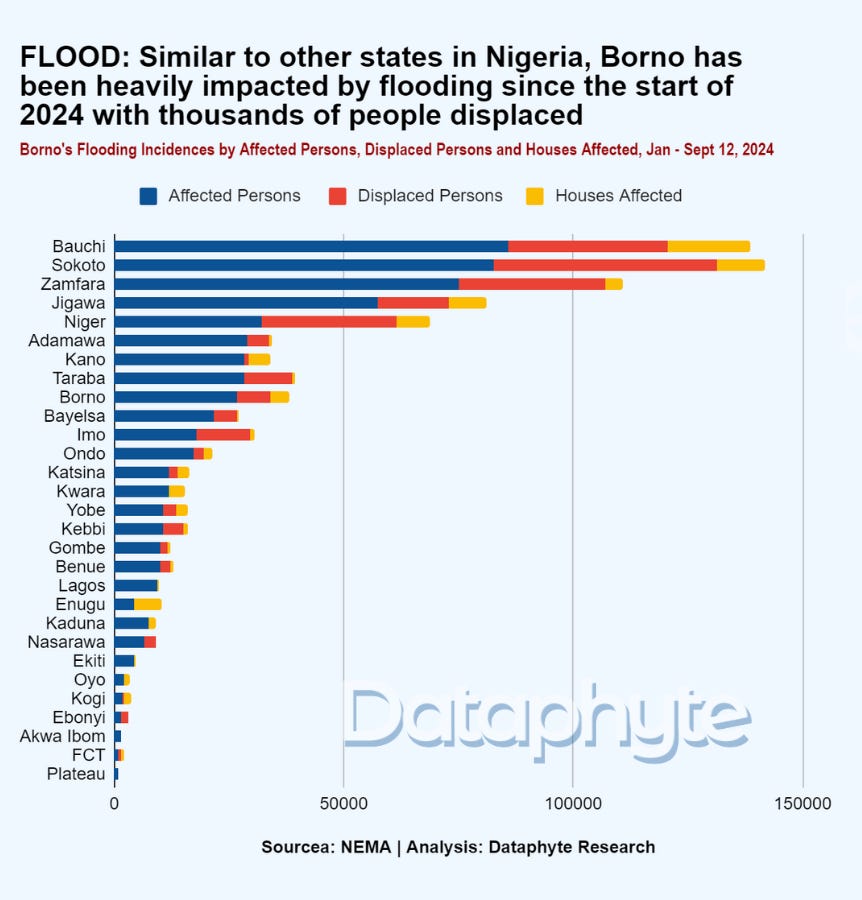

Between January and September 2024, Borno residents have been enduring a wave of distress following a series of floods that resulted in casualties.

Since January, flooding in Borno has affected about Twenty-Seven Thousand (26,687) persons and displaced over 7,198 persons.

Two years before, the floods affected Sixty-Six Thousand (66,216) people in Borno alone. The 2022 floods affected 34 of Nigeria’s 36 states and the Federal Capital Territory.

Four northeast and four northwest states, along with one state each from the south-south and north-central regions, are among the top 10 most heavily flooded states between January and September 2024.

It’s still three months to the end of the year. One may expect more flooding incidents in subsequent days. For instance, the Nigerian Meteorological Agency (NiMET) has alerted Adamawa State over an impending three-day rainfall starting on the 16th of September.

Devastations from flooding in Nigeria usually result from the impacts of climate change, government and stakeholder negligence, or the public's disregard for flood warnings.

Blood

Fela’s reflection on how the actions of the police and army "leave some people losing their bread (or source of livelihood), someone nearly dying, and someone just dying" resonates deeply with the situation in Borno.

Records from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) show that, since 2015, Borno State recorded the highest number of deaths from battles, explosions, and other forms of violence against civilians compared to other states, with 32,388 persons slain in the state.

Confusion Everywhere

Beneath the flooded Maiduguri metropolis, and elsewhere in Borno, someone just lost some means of daily bread, someone’s breadwinner just died, and confusion reigns everywhere.

A United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Report confirms insecurity is both a cause and effect of poor socioeconomic indicators:

“Since 2009, persistent conflict in north-eastern Nigeria has led to the loss of lives and properties, destruction of critical infrastructure, displacement of millions, and the destabilization of economic, health and education systems. These developments have had attendant effects on the productivity and development of the region and the country at large, given scarce national resources…

"The effects of the insurgency and the persistence of insecurity are inseparable from the region’s (northeast) pre-existing socio-economic deprivation and harsh environmental conditions.”

This has left people vulnerable and dependent on humanitarian aid. As of 2022, about 2.25 million people in Borno, or 37% of the population, were living in poverty and struggling to achieve a decent standard of living.

Insecurity frequently causes the destruction and closure of schools, which makes it challenging or even impossible for children to attend. As families escape from conflict, displaced children often lose access to education. Even those who remain may stop going to school because of the threat of abduction.

While broader factors, such as cultural beliefs, may affect people’s perceptions of education, conflicts can significantly diminish educational opportunities. Additionally, disasters like flooding also affect school-aged children’s access to education, as their homes and schools may be destroyed by the flood.

Borno is one of the Nigerian states with a significant number of school-aged children who are not attending school. According to the Multidimensional Poverty Index (2022), over 54,000 children, representing 54 per cent of school-aged children, in Borno are out of school.

In response to the Alau Dam collapse, the Federal Government, through the Federal Ministry of Water Resources and Sanitation, has announced plans for immediate upgrading of the dam.

The government made the same promise after the Alau dam collapsed during the 2022 flooding.

Then, the Managing Director of Chad Basin Development Authority, Mr. Abba Garba, affirmed the government will rehabilitate the dam. He noted: “The Alau Dam’s purpose has been hampered by its recent collapse as a result of the 2022 devastating flood that caused an overload of water from the upstream, leading to structural corrosion and eventual collapse.

“The procurement processes to assess the impact and rehabilitate the dam are currently underway.”

Now, in 2024, the Minister of Water Resources and Sanitation, Engr. Prof. Joseph Terlumun Utsev, said, “We are committed to a thorough overhaul of this critical infrastructure. The Alau Dam upgrade is non-negotiable, and any poor performance by contractors or officials involved will not go unpunished. Sanctions will be enforced for any delays or substandard work.”

Yet, the narrative hasn’t changed.

Even if the dam is repaired, the devastation it has inflicted on households and families will linger for years, and for some, forever. The confusion and loss may become etched into the collective memory of the people.

With manifest scars from years of violence, this new wave of sorrow only adds to the heavy burdens that hang over Borno.

In his closing reflection in "Sorrow, Tears, and Blood," Fela highlighted the deep-rooted fear that often incapacitates the people’s resistance and demand for accountability and change.

He invoked a spirit of resilience and defiance—not just against the brutal operations of the "police and army," but also against the systems that thrive on flawed accountability structures to this day.

The flawed system continues to empower those who benefit from the sustained trauma and confusion of the people of Borno to this day.

A fearful citizenry continues to enable them all.

Fela remarked:

“My people self dey fear too much

We fear for the thing we no see

We fear for the air around us

We fear to fight for freedom

We fear to fight for liberty

We fear to fight for justice

We fear to fight for happiness

We always get reason to fear”