Ensuring Safety and Health at Work in a Changing Climate!

This is the theme of the 2024 Workers’ Day celebration.

It emphasises prioritising the safety and health of workers in all government policies and decisions.

Yet, the safety and health of workers begin with child workers.

The safety of “the 31.3 million incredible women and 40 million amazing men who pour their hearts into every task, every day, shaping their families, communities, and our nation” begins with the safety of every girl or boy who equally works to support themselves or their families.

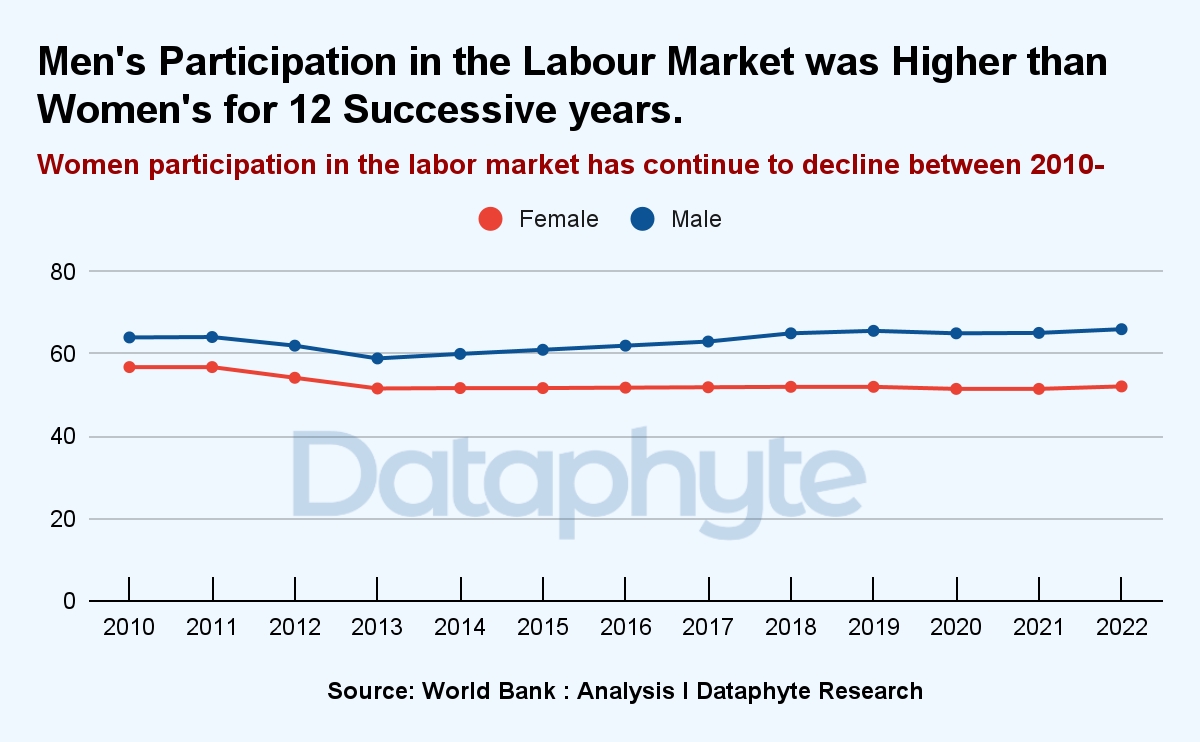

Labour Force: Like Global Men, Like Local Men

Nigeria’s labour force has more men than women.

Nigeria’s local gender gap in the labour force fits the global trend.

A World Bank Report, “Global Gender Gap in the Workforce, shows that the global labour-force participation rate for women is just over 50%, while it is around 80% for men.

The labour force comprises individuals who are employed or fit for employment and able to contribute to the country's economic output.

World Bank data reveals a concerning disparity in the labour market. For the past 12 years, women's recruitment has lagged behind male employment rates.

As of 2022, Nigeria’s labour force participation rate among females was 52.1%, and among males, it was 65.5%. This shows the disparity between the number of males and females eligible to be employed in the Nigerian Labour market.

In 2023, the Nigerian labour force reached over 75.5 million. The previous year, around 73.3 million people were economically active.

At the workplace, the total employed male population in Nigeria is estimated at almost 40 million, while the number of female employees is projected to be slightly lower, at around 31.3 million.

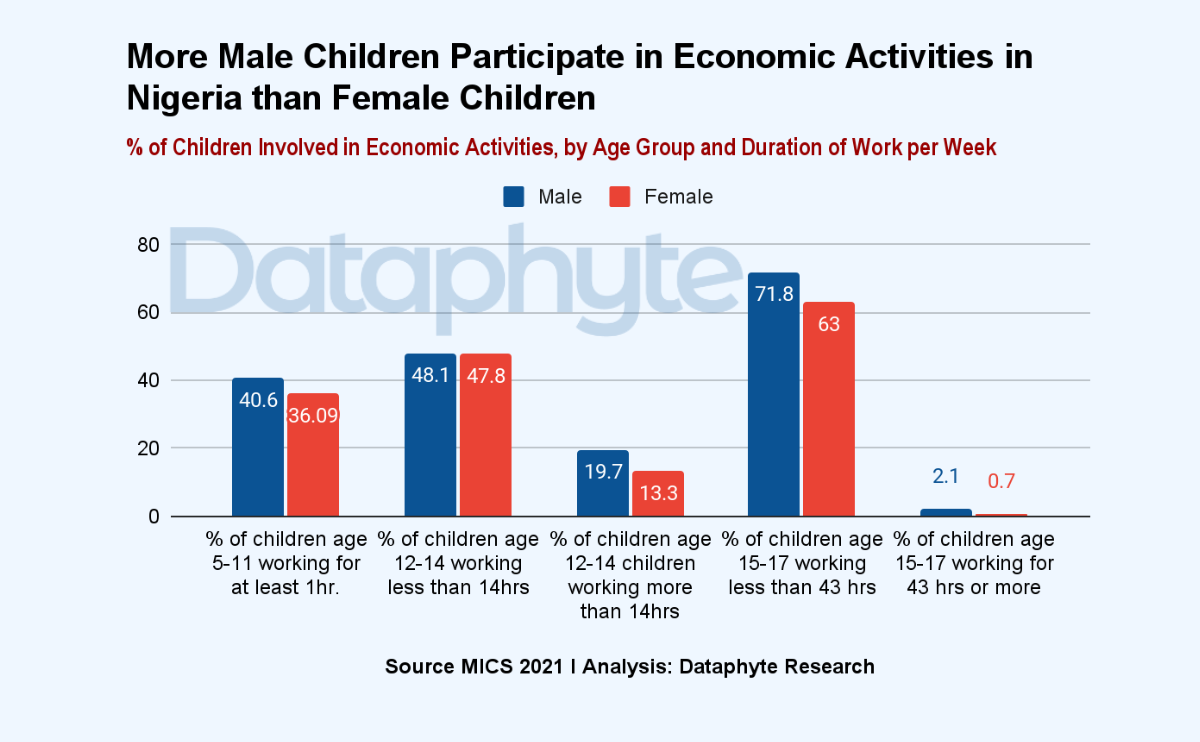

Labour Force: Like Men, Like Boys

More male children engage in economic activities than females, a gender productivity and pay gap that extends into adulthood. This is gleaned from the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) 2021.

The percentage of male children between the ages of 5 and 11 who worked for at least an hour in a week was 40%, compared with 36.1% for female children.

Also, 481 in every 1000 male children aged 12 to 14 work less than 14 hours weekly. However, it is 478 out of 1000 female children of the same age group that work to earn money for themselves or family.

For children working above 14 hours per week, more male children work than female children. The figure here is 197 in 1000 male children and 133 in 1000 female children working above 14 hours per week.

The gender gap continues as the children grow into their latter childhood years, ages 15-17. Here, 718 in 1000 male children work 43 hours weekly while its 630 in 1000 females.

Even with children who work more than 43 hours weekly, the males still lead the labour force. Here, 21 in 1000 male children work beyond 43 hours weekly compared to 7 in 1000 female children.

Ensuring Safety and Health for Child Workers

The term “child labour” is often defined as work that deprives children of their childhood, their potential and dignity and that is harmful to physical and mental development. It refers to work that is mentally, physically, socially or morally dangerous and harmful to children.

The Nigerian Child’s Rights Act( 2003) defines a child as any person under the age of 18 years. It prohibits the engagement of children in any form of labour that is detrimental to their development.

The Act sets the minimum age for employment at 15. However, it provides that children under 14 can be employed, provided that it does not interfere with their education.

Also, the International Labour Organisation (ILO) says that whether or not particular forms of “work” can be called “child labour” depends on the child’s age, the type and hours of work performed, the conditions under which it is performed, and the objectives pursued by individual countries. The answer varies from country to country and among sectors within countries.

However, the ILO Convention No. 138 set the working age at 15, possibly setting the minimum age at 14 for countries with insufficient economic development and where educational facilities are insufficiently developed.

International standards also recognise a minimum age for light work that does not interfere with the child’s education – with limited daily and weekly working hours and light activities. It should temporarily be at least 13 years of age – or 12 for insufficiently developed countries.

According to international standards, all forms of hazardous work are forbidden before the age of 18.

The Labour Act says that the minimum age of admission to employment is critical in protecting children from all forms of child labour and exploitation. It also considers the positive dimensions of adolescents' contribution to society in conditions that do not impair their development, health, and education.

Why do Males Work More than Females?

A central element in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is the promotion of productive employment and decent work for all (Goal 8). This is regardless of gender differences.

However, males continue to engage in more paid work than women for certain reasons. These are listed below.

Labour Force Participation Rate: Between 2019 and 2020, the global women’s labour-force participation rate declined by 3.4%, compared to 2.4% for men. However, since then, women have been (re-)entering the workforce at a slightly higher rate than men, resulting in a modest recovery in gender parity.

Formal Employment Opportunities: Women are less likely to work in formal employment settings. They often face barriers such as gender stereotypes, discrimination, and limited access to quality education and training. These factors can restrict their opportunities for career progression and business expansion.

Gender Norms and Expectations: Societal norms and expectations play a significant role. Traditional gender roles may discourage women from pursuing certain careers or working full-time. Men, on the other hand, may face less pressure to prioritise caregiving over their careers.

Maternity Leave and Family Policies: Maternity leave policies vary globally. Some countries offer longer paid maternity leave, while others provide limited support. The fear of career setbacks due to taking time off for childbirth can influence women’s decisions about employment.

Discrimination and Bias: Discrimination based on gender remains a barrier. Women may encounter bias during recruitment, promotion, and salary negotiations. Stereotypes about women’s commitment to work after having children can also affect hiring decisions.

Sectoral Differences: Men and women often work in different sectors. Some industries, such as technology and engineering, have fewer female employees. Encouraging women’s participation in male-dominated fields can help bridge the gap.

Access to Education and Skills Development: Unequal access to education and skills development programs can limit women’s career prospects. Investing in women’s education and training is crucial for narrowing the employment gap.

Addressing the gender gap in employment requires a multifaceted approach, including policy changes, cultural shifts, and efforts to challenge stereotypes and biases.

By promoting equal opportunities and supporting women’s career advancement, we can work toward a more equitable workforce.

SenorRita Ponders🤔

Do males really work more than females?

The answer may be “No”.

The gender gap in employment is a complex issue influenced by various factors.

When employment is defined as work performed in return for pay or profit, men appear to work more than women.

However, when employment includes work done with or without pay, women may be seen to work more than men do.

Women often shoulder a disproportionate burden of unpaid care work, including childcare, eldercare, and household chores. Balancing these responsibilities with paid employment can be challenging, leading some women to opt for part-time or flexible work arrangements.

That’s what SenorRita thinks.

What do you think?

We hope you enjoyed this Worker’s Day Edition of SenorRita. It was written by Kafilat Taiwo and edited by Oluseyi Olufemi.