We are in that unique month when women and mothers are celebrated globally.

March 8 was World Women’s Day. March 10 was Mothering Day, as are many other days in the year.

Many agree they deserve these and more.

The traditional idea of motherhood has been evolving. It is being shaped by shifting societal norms, economic demands and new cultural expectations.

Mothers are the foundational support of every new life and keep sustaining infants until they are weaned.

They school the toddlers till they can feed by themselves, and many times, they slave to provide for the grown-ups till they come of age to fend for themselves.

What we can’t ignore today is the increasing number of women who provide the proverbial daily bread when our fathers on earth no longer give us our daily bread.

Breastfeeding

According to UNICEF, there is a rising prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding in Nigeria.

As of 2021, Nigeria has a prevalence of 34.4% of exclusive infant breastfeeding of 6 months and below.

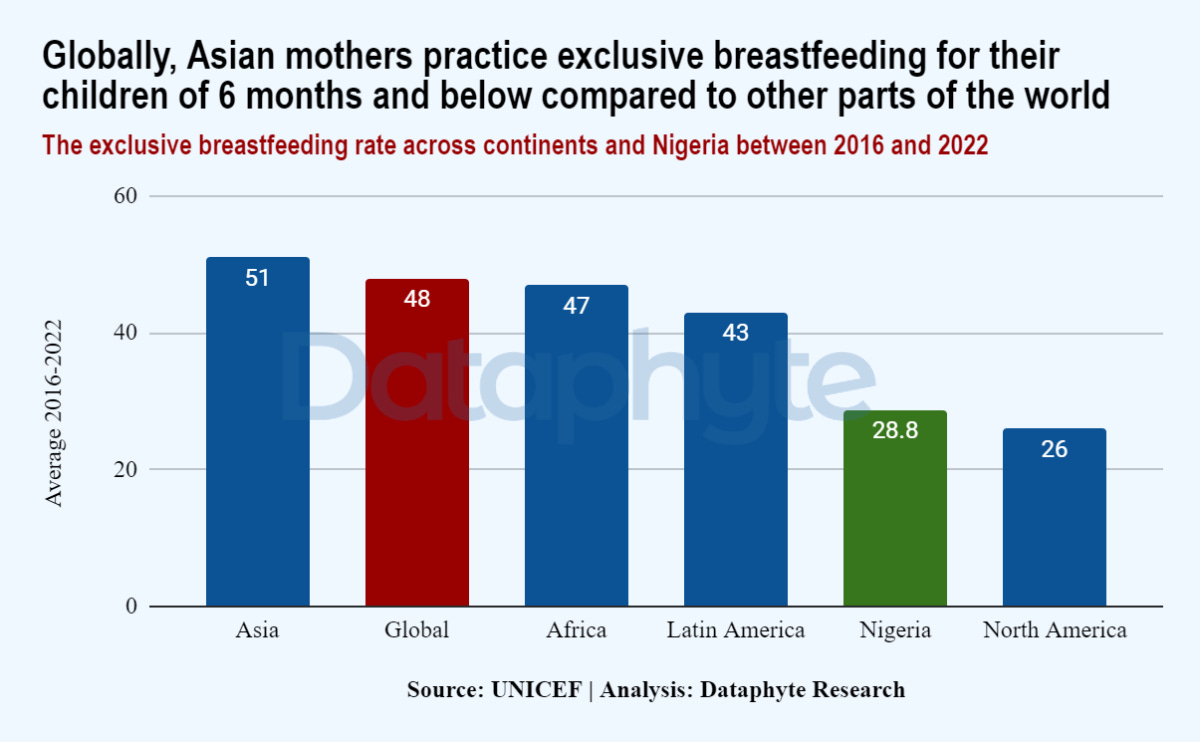

Globally, the average prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding of infants of 6 months and below is 48%.

Asian women have the highest average of exclusive breastfeeding in the world, while North America has the lowest average breastfeeding of infants of 6 months and below.

Despite the rising prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding in Nigeria, Nigeria’s average exclusive breastfeeding is below the global and Africa’s average.

Among mothers, the paid working mothers who work or provide services for others outside the family have less time to breastfeed their babies.

For instance, in Nigeria, there is a low prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding among female medical doctors. A study, “Breast Feeding Practice among Medical Women in Nigeria” by A. E. Sadoh and others, shows that only 11 in 100 medical women exclusively breastfeed their babies.

Among the myriad roles a mother has to fulfil, a working breastfeeding mother stands at the intersection of their industrial demands and maternal instincts — balancing career aspirations with nurturing their offspring.

The call for gender equity, especially in the workplace, highlights the vulnerability of breastfeeding mothers who are caught in the dilemma of staying at home to breastfeed their newborn adequately and quickly returning to work to ensure the economic security of their families.

A mother’s dilemma is more pronounced in professions and jobs that mandate her to choose between breadwinning and breastfeeding.

Breadwinning

Africa has the world's highest number of female-headed households, where the woman is the main breadwinner.

Eritrea has the highest percentage of African female-headed households, at 46.7%. Followed by countries such as Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe.

Nigeria has a low prevalence of women being the major breadwinner of their families.

Analysis of World Bank data shows that between 15 and 20 per cent of mothers were the main breadwinners of their families in Nigeria from 2003 to 2021.

In short, 17 in 100 women in Nigeria are sole or primary breadwinners - single mothers, married, divorced or widowed women - bringing in most of their families’ earnings, as of 2021.

This shows a lower prevalence of females being sole or primary breadwinners of homes in Nigeria.

Traditional cultures and religious beliefs contribute to this low prevalence of females being the sole breadwinners in Nigeria.

Most Nigerian men are taught to provide and take care of their families from a tender age.

While this does not seem to be a significant percentage of Nigeria’s female population, there is an upward trajectory of mothers becoming breadwinners in recent times.

Between 2014 and 2023, household incomes declined in Nigeria, making more women join the labour force or start their businesses to become co-breadwinners of their families or increase their earnings as sole breadwinners.

Women in the Labour Force

Globally, the participation of women in the paid labour force has remained flat over the last three decades - fluctuating between 47% and 49%.

At the intercontinental level, Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest number of women active in the labour force compared to other continents. On average, in Sub-Saharan Africa, 6 out of 10 women work.

In Nigeria, 52 out of 100 women are part of the active labour force, as of 2023. This is a drop from 56 out of 100 women in 2014.

Though Nigeria’s female population actively engaged in the paid labour force has declined, it still exceeds the global average.

However, though the proportion of women joining the formal labour force is less than that of men, many more women work in the informal or unaccounted sectors of the economy to increase their earnings.

A report by the International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that the Nigerian economy constitutes 93% of the informal sector, of which women run 95% of the sector compared to 90% of their male counterparts.

This indicates that more women are engaged in some form of economic activity outside the home, which is unaccounted for by the World Bank data on the female working population.

Few women leave the labour force during their childbearing and child-raising years because of the increasing need to financially support their families. Also, the cost of interruption in their career is so high that they do not dare to withdraw from the labour force even when they have children.

Work and Family Balance

A study by the Grattan Institute discovered that income gaps between fathers and mothers are due to women reducing paid work to take up more household work.

Mothers reduce their paid work hours to take on a greater share of caring for the kids and household work. The change is less dramatic for the fathers who continue their paid work and take on only some household work and caring.

More women are finding ways to balance their work and family obligations.

Surveys conducted in Australia on pregnancy and childbirth's impact on work show that fewer women are leaving work after childbearing because they stand a lower chance of getting their jobs back after taking a long leave of absence from their jobs.

Women are the most vulnerable to gender inequities at work, especially after childbirth.

Women face the risk of being dismissed, inability to rest and heal after giving birth, unhealthy and unsafe working conditions and environments, and so on when transitioning from childbirth to work.

Over the years, international communities such as the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the World Health Organization (WHO) have been pushing to encourage maternity protection in countries worldwide.

How Do We Make Women’s Lives Better?

Women are one of the people most vulnerable to gender inequities at work, resulting in higher poverty levels.

Currently, policies to encourage the protection of women in the workplace, especially for women nursing their infants and toddlers, are being advanced in the Sustainability Development Goals (SDG).

Policies such as Maternity Protection schemes, which include maternity leaves, cash benefits, protection from unhealthy and unsafe working conditions and environment, safeguard employment, protection against discrimination and dismissals, and allowing them to return to work taking into account their specific circumstances, including breastfeeding, would go a long way in protecting women who give birth. As suggested by ILO.

There have been some advancements in ensuring maternity protection around the world. Currently, 111 countries out of 192 countries provide at least 14 weeks of paid maternity leave.

Nigeria is one of the countries that encourage women to take paid maternity leave of 12 to 13 weeks.

Many are promulgating the need to include paternity leave with paid benefits to encourage men to participate more in domestic work while their women are nursing babies, and to bond with their spouse and family.

Other like-policies, such as closing the wage gap between men and women and increasing enrollment of the girl-child in schools to improve their chances in life, can create more equal opportunities for women.

Women can have it good - work, life and family - breastfeeding, breadwinning and everything in between.

Hope you enjoyed this edition of Data Dive. It was written by Lucy Okonkwo, who wants to have a share of work and homemaking and a soft life in between. It was edited by Oluseyi Olufemi, who feels it’s time to begin appreciating and compensating women for their work at home.