Remembering Rwanda

On April 7, 1994, the pockets of mutual interethnic hostilities between Hutus and Tutsis morphed into a genocide of historical proportions.

The ethnic cleansing did not come as a surprise, regardless of the debates over it being systematic or sporadic in execution.

It bore the same strain of subrational cruelty and mass hysteria that seedlings of mistrust and hate bear when their demons mature.

And Rwanda’s mass fratricide was rooted in the same existential causes as other large scale mortal betrayals - unmitigated social injustices, economic inequities, and political struggles.

These 3 causes and the overlapping diminished social cohesion measure how fragile a state is, according to the Fund for Peace.

To the unsuspecting observer, these triad of tragedies are often masked in a cloak of racial, ethnic, or religious superiority.

A commentary on this deception in Rwanda, 30 Aprils ago, has it that:

“To make the economic, social and political conflict look more like an ethnic conflict, the President's entourage, including the army, launched propaganda campaigns to fabricate events of ethnic crisis caused by the Tutsi and the RPF. The process was described as "mirror politics", also known as "accusation in a mirror" whereby a person accuses others of what the person himself/herself actually wants to do.”

This same tragedy eventually evolves everywhere these lies are conserved, from Burundi and Rwanda to Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The genocide, an immediate development from the Rwandan Civil War, saw the Hutus target the minority Tutsi population for annihilation through the vilest murders and ancillary afflictions like public rape and mass infection of surviving Tutsi women with HIV/AIDS.

These horrors lasted 100 days, between April 7 and July 19, 1994, leaving in its toll 800,000 murdered souls and mutilated bodies, mostly of ethnic Tutsis, and moderate Hutus and Twas.

An estimated 250,000 to 500,000 women were raped, and over 2 million displaced.

Thirty years after the genocide, Rwanda continues its efforts at recovery to ensure the state is less fragile. It continues rebuilding a country that is less vulnerable to a crisis situation like the 1994 episode.

Rwanda still has a long way to go. So are the other 53 divided states of Africa.

Remembering Rwanda offers all a time to reflect on the social, economic and political challenges of their communities, counties, and countries.

It’s a time to reflect on the arguments that each suffer because their neighbour was born by an accident of nature into the other ethnic group or into the family of adherents of the other religion.

It’s a time to rethink the elites wearing ethno-religious coats on their naked ineptitude to deliver things so basic to a more cohesive and less chaotic life for all.

It's time to ask: How fragile is my community? How fair is the social, economic, political systems in my county? And how far is my country today from April 7, 1994, somewhere in Rwanda?

Rwanda: How Fragile?

Rwanda’s road to stability has been slow but steady, judging by its State fragility in the last 18 years.

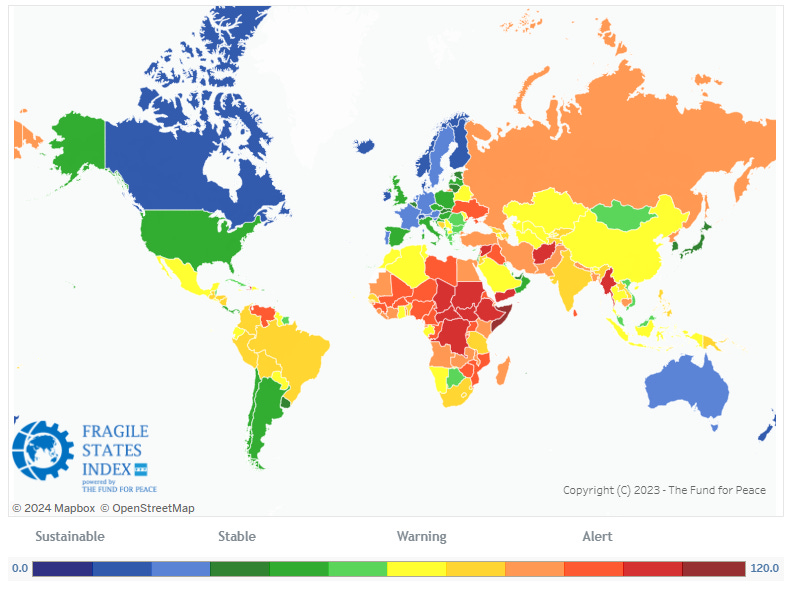

The Fragile States Index, measured by The Fund for Peace, shows that civil war or genocide is less likely to occur in Rwanda now than it was before.

The country’s 2023 state fragility score is the lowest and best in the last 18 years.

On the global ratings, Rwanda is the 44th most fragile country out of 179, with a fragility score of 82.3 out of 120.

This indicates that Rwanda is not out of the woods yet but is working hard to ensure the country never experiences another major upset.

Its highest and worst score in the last 18 years was in 2006, 12 years after the 1994 genocide. Then, the country recorded a high fragility score of 92.9 out of 120, ranking as the 24th most fragile state in the world.

According to The Fund for Peace, “The fragility State Index measures the vulnerability of states to collapse.” The Index is measured by summing up each country’s score in 4 key indicators. The score for each indicator is also the sum of its 3 sub-indicators:

Lack of Cohesion

One of the factors that spurred Rwanda’s genocide in 1994 was the ethnic divide, which pre-dated the country’s independence in 1962.

Also, the history of the genocide revealed that the armed forces were factionalised - the Hutu majority government armed forces and the rebel Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) led by Tutsi exiles in Uganda.

In 1993, hardline Hutus launched their Radio Television Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM) radio channel. The channel was used to incite hatred towards the Tutsis by using propaganda and racist ideologies such as the Hutu Ten Commandments.

These funded and fanned embers of Hutu hatred against Tutsis led to full scale genocide in April 1994.

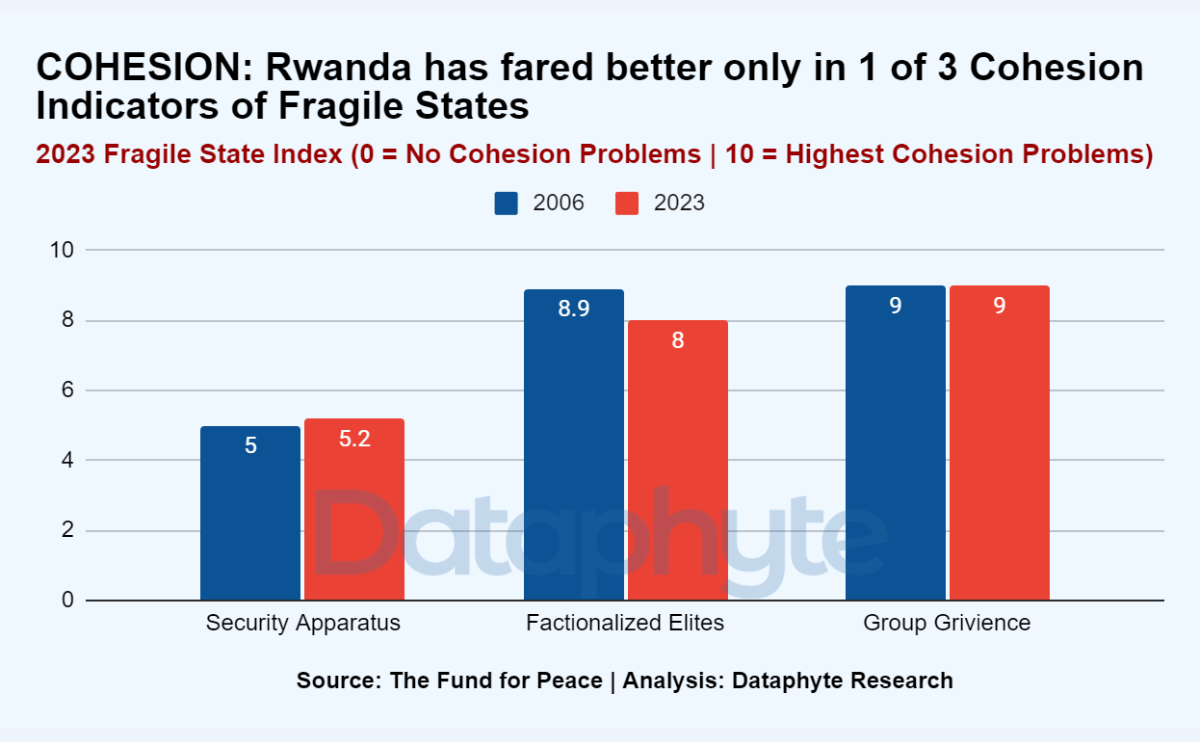

Currently, the country is becoming more cohesive. Its threats to cohesion score was reduced from 22.8 in 2022 to 22.2 in 2023 out of 30. (0 = No Cohesion problems; 30 = Highest Cohesion problem).

Under the Cohesion Indicators, Rwanda’s Security Apparatus score is 5.2 out of 10. This indicates that Rwanda is a moderately secure state. The security threat level from rebel force movements or militias is not very high, and the citizens have a measure of trust in domestic security.

The Factionalized elites score of Rwanda is 8 out of 10.

According to the Fund of Peace, “The factionalised elite indicator measures the fragmentation of the state institutions along ethnic, class, clan, racial or religious lines… It also factors the use of nationalistic political rhetorics by ruling elites, often in terms of nationalism, xenophobia, communal irredentism… or communal solidarity (e.g., “ethnic cleansing” or “defending the faith”).”

The factionalised elite indicator is measured considering the questions around identity:

National Identity: Is there a sense of national identity? Are there strong feelings of nationalism? Or are there calls for separatism?

Extremist Rhetorics: Does Hate Media and radio exist?

Stereotyping: Is religious, ethnic, or other stereotyping prevalent, and is there scapegoating?

Cross-cultural Respect: Does cross-cultural respect exist?

The high score implies that there is still a high measure of fragmentation among the ethnic groups in Rwanda.

Their score on group grievance is the highest among the cohesion indicators: 9 out of 10. This implies that there is still a very high number of aggrieved groups in Rwanda.

While we worry about Rwanda, Nigeria currently fares worse in all cohesion indicator scores, except with group grievance. It is doing worse than Rwanda in (in)security and factionalised elites.

This implies that Nigeria faces a high chance of internal security threats. There is a high possibility of further insurrection by ethno-religious or sociocultural groups that may destabilise the country.

Also, the factionalised elite score corroborates the divisive tendencies in the polity. It is the highest score among the cohesion indicators. This indicates that there is tension within the leadership of different ethnic, religious and sociocultural groups in Nigeria than in Rwanda.

Nigeria needs to be very concerned about the implications of these scores.

Considerable progress has been made in ensuring cohesion, especially with regard to national identity, “but among Rwanda’s older generation, the fear of a resurgence of ethnic tensions remains alive. Many within the Rwandan government are concerned that not enough time has passed to foster a unified identity that can fully expel an ideology that wrought so much carnage.”

In June 2008, the Rwandan parliament introduced a new law that criminalised genocide ideology. Article 3 of the law specifies the criteria for the crime of genocide ideology.

“The crime of genocide ideology is manifested in any behaviour characterised by evidence aimed at depriving a person or a group of persons of common interest of humanity like in the following manner:

1. threatening, intimidations, degrading through defamatory speeches, documents or actions which aim at propounding wickedness or inciting hatred;

2. marginalise, laugh at one’s misfortune, defame, mock, boast, despise, degrade, create confusion aiming at negating the genocide which occurred, stirring up ill feelings, taking revenge, altering testimony or evidence for the genocide which occurred;

3. kill, planning to kill or attempting to kill someone following the genocide ideology.”

Economic Threats

Rwanda has significantly reduced its economic threats in the past 17 years. It has reduced its economic threat levels from 23.4 in 30 in 2006 to 20.3 out of 30.

Currently, the highest score among its economic indicators is Uneven economic development, which rose from 7.2 out of 10 in 2006 to 7.8 out of 10 in 2023.

The uneven economic development measures the level of economic inequality in Rwanda. This indicates that economic inequality is rising slowly in Rwanda.

The Fund of Peace notes that “the uneven economic development indicator considers the different forms of inequality in the nation’s economy, including group-based structural inequality, such as racial, ethnic, religious, or identity groups.”

One of the factors that triggered the Rwandan genocide was the exclusion of the Tutsis from prominent careers and the implementation of education quotas by the Hutu consolidated government.

Rwandans may not have to worry so much about economic inequality between ethnic groups now, but like every other country, it has a nagging worry: class inequality.

According to Helen Hintjens, in her publication on Post-genocide identity politics in Rwanda, there is worsening rural poverty.

“The social distance between urban elites and small-scale peasant producers is probably greater than before the genocide. Landless rural families live in extreme poverty, with recurring food shortages now affecting some regions. Many of the poor lack even basic access to health care and education.”

Nigeria records higher economic indicators of a fragile state than Rwanda. The high economic threats score indicates that Nigerians suffer from decreased opportunities for optimal productivity and prosperity and the attendant increased poverty rate.

This is coupled with uneven distribution of resources currently among the different classes of Nigerians than the case is with Rwandans.

We will continue this discussion next week.

Thanks for reading this Data Dives. It was authored by Lucy Okonkwo and edited by Oluseyi Olufemi.