Remembering Rwanda (2)

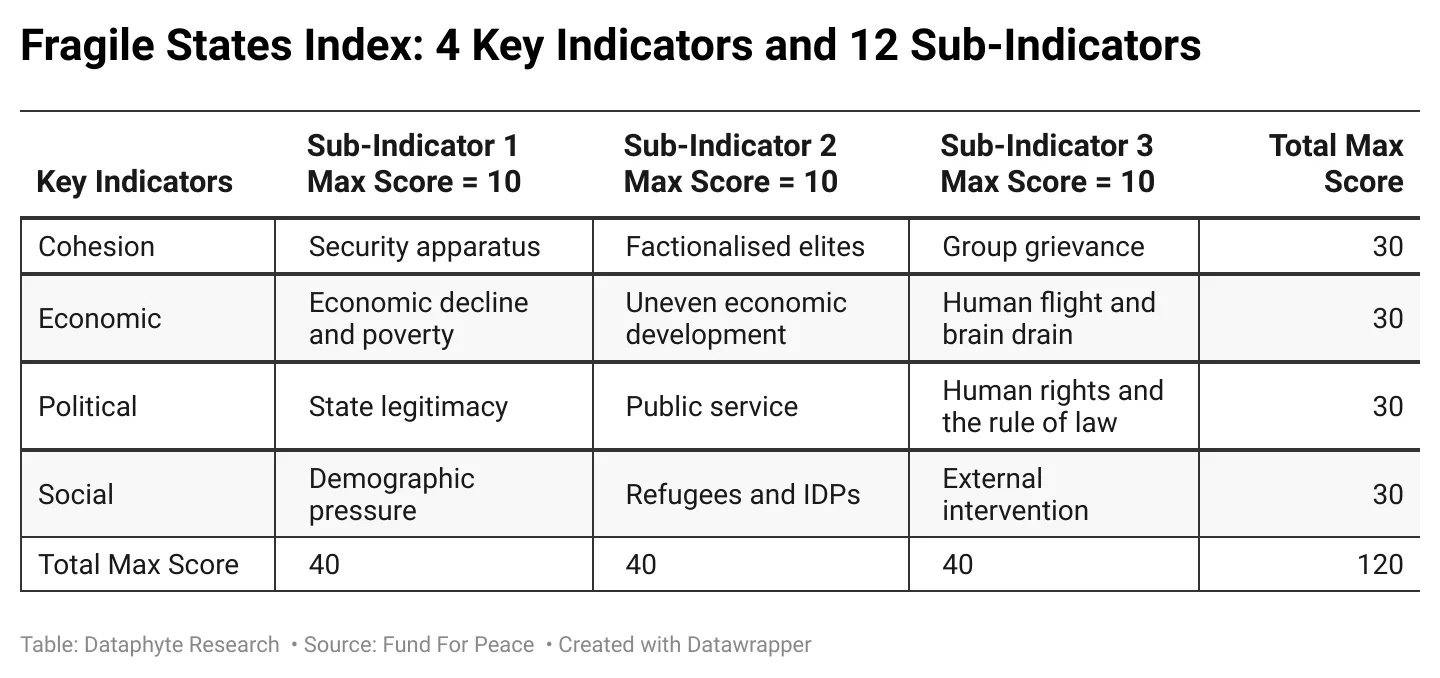

Again, to remember Rwanda is to reflect on how the country’s fragile socio-political system made it susceptible to a full-blown humanitarian crisis as the 1994 genocide.

As with Rwanda and its African peers, the cracks in their social systems and weak(ened) political institutions have resulted in factionalised elites and group grievance and the attendant rise of ethnic militias, sectarian violence, and other terrorism threats.

Howbeit, Rwanda’s post-genocide responses show us how purposeful leadership can reduce social tensions and reinforce political institutions.

After the martial victory in July 1994, the Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF) organised a coalition government led by Paul Kagame.

Under President Paul Kagame, the Rwandan government has worked on policies that promoted reconciliation, maintained security, and ensured justice for the affected people.

Also, considerable progress has also been made in including women and youth in politics. According to Intra-Parliamentary Union (IPU) data, Rwanda has the highest number of women representatives in government globally.

There are 61.25% of women representatives in the Rwandan Government.

However, many critics of the Kagame government have accused it of having “highly centralised political power, nonexistent political opposition, weak civil society, and limited media freedom.”

Despite possible flaws in its methods, the Rwandan government has continued to build political systems that will ensure it is less susceptible to political situations that trigger crises like the 1994 Genocide.

Beyond Rwanda, African States remain very fragile.

In the last 4 years, there have been threats to democracy in Africa - the emergence of coups, controversial elections, and a clampdown on political inclusion.

These questions linger from our last read on Rwanda:

How fragile is my community?

How fair are the social, economic, and political systems in my county?

And how far is my country today from April 7, 1994, somewhere in Rwanda?

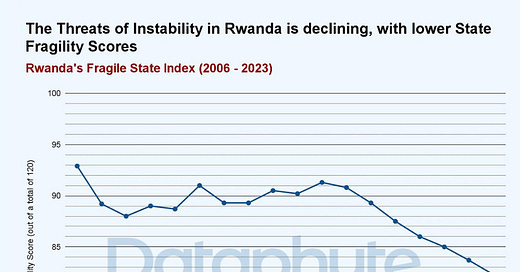

Rwanda: Less Fragile

Besides Rwanda’s conflicted ethnic and economic history, there were extant political and social vulnerabilities that weakened the polity and finally broke the fragile state in 1994.

Its political fragility ranked as one of its highest threats as of 2006 but ranks the least of its troubles as of 2023, its Fragile State Sub-Indices shows.

This shows that the reduction in the country’s overall Fragile State Index is due to a significant reduction in its political, economic, and social threats and little reduction in the incohesive state of ethnic and elite relations.

Further analysis reveals that the fragility problems Rwanda wrestled with in the 18-year period reviewed were social and lack of cohesion threats.

The easiest problems the government was able to tackle were political and economic threats, going by the average score of the sub-indices.

However, Kigame’s 25-year-long government appears to have no concrete answer to the (in)cohesion question. Problems with group grievance and factionalisation remain as much as with the country’s security apparatus.

Political Threats

Rwanda has made progress reducing its 3 main political threats in the past 18 years.

The score for human rights and the rule of law in Rwanda improved, reducing the threat level score from 7.7 in 2006 to 6.2 in 2023.

This indicator shows a decline in human rights abuses and better adherence to the rule of law by the Rwandan government.

According to the Fund of Peace, the Human Rights and Rule of Law indicator measures:

“The outbreaks of politically inspired (as opposed to criminal) violence perpetrated against civilians.”

“It looks at factors such as denial of due process consistent with international norms and practices for political prisoners or dissents, and whether there is current or emerging authoritarian, dictatorial or military rule in which constitutional and democratic institutions and processes are suspended or manipulated.”

The 1994 Genocide had too many people charged for war crimes. Many perpetrators were persecuted either by the International Criminal Court or the local Rwanda Gacaca court.

The 2011 Human Rights Watch publication on the Gacaca showed that many prisoners received an unfair hearing. “There were limitations on the ability of the accused to defend themselves effectively; numerous instances of intimidation and corruption of defence witnesses, judges and other parties; and flawed decision-making due to inadequate training for lay judges who were expected to handle complex cases.”

On state legitimacy, its score is 6.7 out of 10. This suggests that the Rwandan government enjoys a relatively high legitimacy, as Kagame obtained 95% of the vote.

“On the other hand, all viable opposition had been eliminated through house arrests, false accusations of divisionism and so forth. The vote for Kagame in the presidential elections was not surprising, given his complete stranglehold over the levers of state authority and the widespread intimidation of opponents,” reports Helen Hintjens

“Far from supporting the regime, most Rwandans fear it; the political climate has deteriorated, with assassinations and disappearances of opposition politicians increasing since 2003.”

Yet, in all (three) points of political threats, Nigeria is worse off.

This implies that Nigeria faces problems with government legitimacy, the abuse of government office, and high human rights abuse.

The Kagame government has been described as an ethnic autocracy by many of its critics because the Tutsis (who make up just 10% of the entire Rwandan public service) take up the majority of top government positions in the government, especially in the military.

Despite the criticism, the perception of the citizens of Rwanda of their government is better than Nigerians of theirs.

Social Threats

Rwanda’s highest fragile state score for social threats as of 2023 is Refugees and IDPs.

It is also the only 1 of the 3 social indicators whose threat score has increased between 2006 and 2023.

“The indicator measures the Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) and Refugees by country of origin, which signifies internal state pressures as a result of violence, environmental or other factors such as health epidemics.”

It was recorded that during the genocide, 2 million people were displaced either internally or as refugees in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

In recent times, Rwanda passed a bill that will encourage irregular asylum seekers to their country from the UK. The Safety of Rwanda (asylum and Immigrant) Act will make Rwanda a home to other refugees. This will increase Rwanda's refugee and IDP scores in the near future.

Some in the UN have argued that this might not be a great decision, and they wonder if Rwanda has enough jobs, facilities, and resources to accommodate this new incoming population. This will eventually increase the demographic pressure on the available resources.

Unlike the Refugees and IDPs threats, Rwanda's Demographic pressure score has greatly declined in the last 18 years, reducing by 2.3 points.

The demographic pressure indicates that the growing population in Rwanda is still sustainable. This implies that citizens have better access to safe water, food supply, life-sustaining resources, and health care and have lower disease and epidemic prevalence.

The average Rwandan's life expectancy is 69.6 years. While their population has increased by 4.51 million in the last 17 years.

The Rwandan government has created an environment where citizens have easy access to facilities and resources, which has increased their life expectancy and population.

Rwanda has been receiving less intervention from foreign countries or agencies. Rather, they are intervening in other countries, especially neighbouring countries like DRC.

Here, Nigeria lags behind. With a 9.6 threat level out of 10 in demographic pressure, the Nigerian society ranks among the most fragile in the world.

The fast-growing Nigerian population puts pressure on the limited food supply, health care facilities, and other socio-economic resources.

The Nigerian population is estimated to be over 210 million and is still expected to keep rising.

However, the government of Nigeria may worry less than Rwanda’s about the 2 other social threats: Refugees and IDPs and External Intervention.

Lessons for Africa

Most African states are still fragile and very vulnerable to a crisis that can cause a collapse.

Countries like Nigeria, which in recent times has seen the emergence of IPOB, Oduduwa People’s Agitators, and other ethnic group uprisings, should take a lesson from the tragedy of the 1994 genocide in Rwanda.

The Rwandan Genocide left its trails of death, scars of rape, broken nerves, and unresolved hurts.

However, the country has made considerable progress in maintaining peace within its borders, especially among the ethnic groups, while sustaining its economic growth.

Ten years ago, at the 20 years commemoration of the Rwandan Genocide, Zack Beauchamp wrote:

“Perhaps most ominously, a statistical assessment of the risk of state-led mass killing puts Rwanda in the top 15 percent of countries most likely to see mass killing. Sadly, there's no reason to stop worrying about Rwanda even 20 years after the genocide.”

Beauchamp saw the possibility of another state-led mass killing in Rwanda after the 1994 mass killing as it is ranked among the top 15% of countries prone to mass killings then.

By Beauchamp’s estimates, the chances of a state-led mass killing are higher in Sudan, Egypt, South Sudan, Somalia, Mali, Central African Republic, Congo Kinshasha, Guinea, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Guinea Bissau, Cameroon, and Uganda than in Rwanda.

All of these were just 20 years after the Rwandan Genocide.

How fragile is Rwanda now, 30 years after?

How far is Africa from April 7, 1994, somewhere in Rwanda?